[Forthcoming in The Lantern] This is Fine, Right?

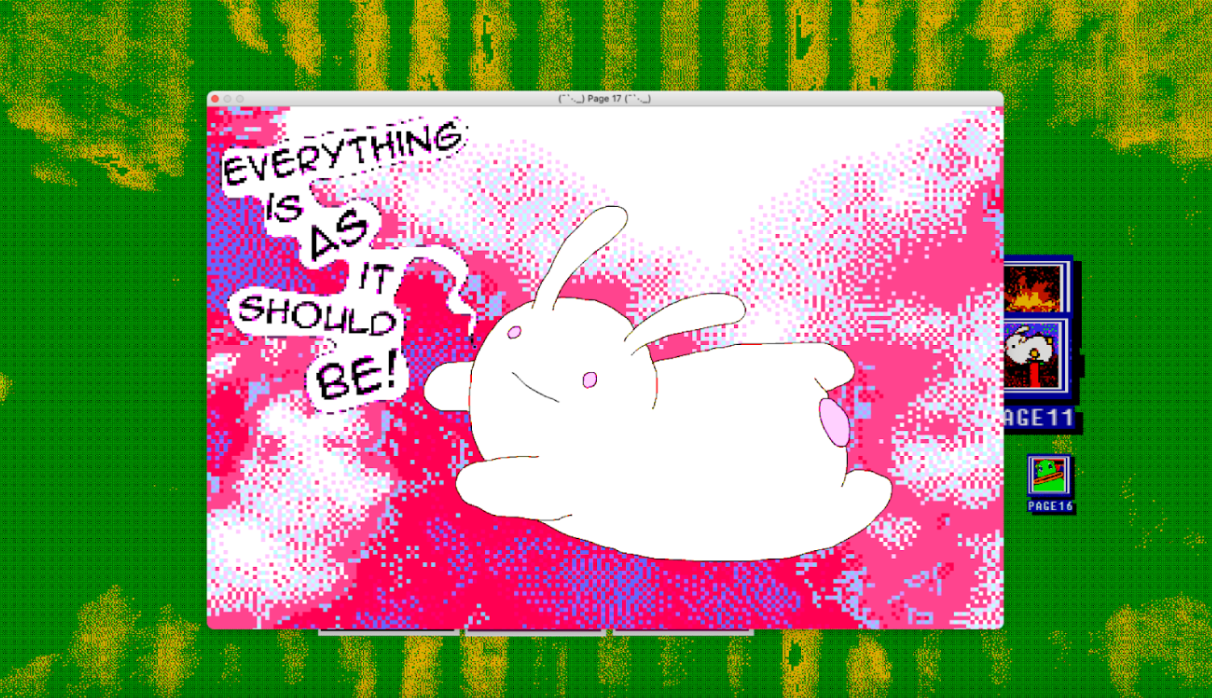

Nathalie Lawhead’s Everything is Going to Be OK is a kaleidoscopic narrative of trauma and survival within a hypermediated world

I am watching an ill-fated bunny fall from the sky and into a field of flaming spikes. My attempts to help the bunny are futile; all I am able to do is click the computer screen in front of me and watch as the animal bounces around, getting impaled dozens of times. Yet it does not ask for my help; it only continuously shouts phrases like “Bliss!!” and "Life is beautiful” with each new injury. Eventually, a pop-up window asks me if I am having fun. My guilt, growing with each new torturous click, pushes me to click “no,” and the scene in front of me disappears.

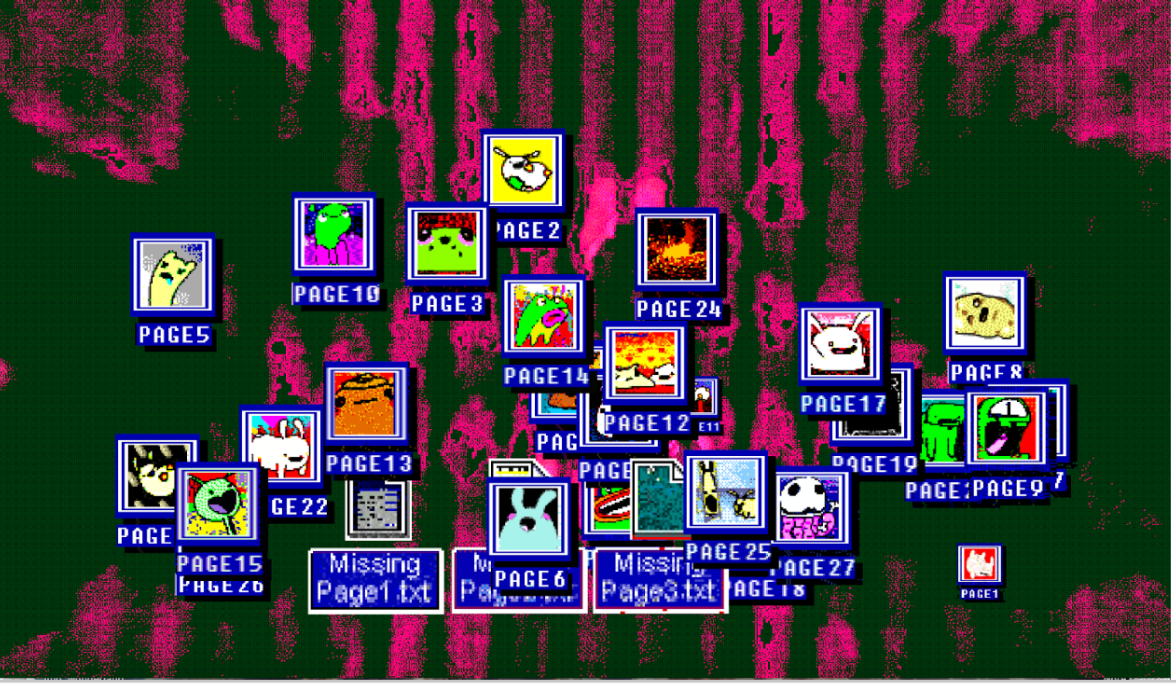

So begins the first page of Nathalie Lawhead’s 2017 digital interactive zine and art game, Everything is Going to Be OK. Released as a free download for computers, the zine comprises 27 individual “pages,” each page functioning as a separate window and interactive storyline. The pages aren’t linear; users can play them in any order and still be able to piece together the central themes of the zine.

In an artist statement, Lawhead described the pages as a “collection of very abstract life experiences, things I felt while going through hard times, and how I felt, or moved on, afterwards.” The distinct pages oscillate between bleak humor and outright horror: cute cartoon animals enduring both hardship and grotesque violence. As a reader and an active player, you’re often powerless to alleviate their suffering.

Opening the zine bombards the user with oversaturated graphics and scratchy audio samples of disparate sounds. The background of the home screen flashes hallucinatory designs, making it hard to know what to focus on and what not to. It is all a bit dread-inducing, and the only relief you get comes from opening one of the floating page icons on the screen.

As you play through the pages, it becomes clear that they each contain their own universes of nightmares. Rejection occurs as a theme over and over; in page three, you play as a bunny that gets repeatedly rejected by its romantic interests, despite attempts to win over its crushes. Page six features a similar scenario; you are tasked with making friends for one of the cartoon animals on-screen, only to be refused at every turn. Many pages feature characters who seem to have entirely given up on life. In page 11, for instance, a bunny impaled on a spike begins expressing its suicidal ideations. You’re given five seconds to select pre-written phrases to try and convince it that its pain is temporary. No matter what you say, the bunny only continues to sink further down the spike despite your best attempts. The scene’s inevitability underscores a recurring truth: you never really had the power to save them.

Lawhead plays with the concept of choice throughout the zine, giving users some agency over immediate actions but withholding their ability to change harsh final outcomes. In their artist statement, they wrote that the zine is “oddly enough, my own power fantasy. I have come to think we have a backward idea of power...Power is viewed as how many people you can subjugate.” The pages frequently depict characters in powerless situations, challenging conventional narratives of strength. Lawhead asks, “What is it like for survivors? Are people who live with trauma strong?” The questions Lawhead poses implicitly critique the cultural tendency to hush pain with hollow words and cliche platitudes.

In page 21, for example, a character loses all their legs and cries for help from bystanders. Yet the bystander’s responses range from a begrudging “Have you ever considered self-help?” to “You just have to believe in and take charge of your life” or a dismissive, “Hmm, fascinating.” This is a satirical portrayal of a culture that both denies emotional hardship and commodifies suffering into feel-good inspiration for others. As both the reader and player, it is hard not to feel complicit as these moments play out in front of you.

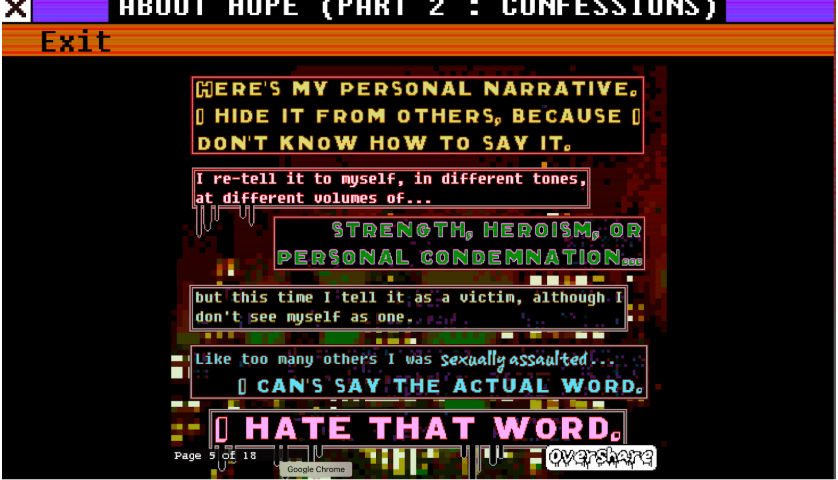

While the zine reflects broader musings on survival and suffering, the dialogue between characters is often so specific that it feels as though Lawhead is speaking through the characters they created. In 2018, Lawhead updated the zine to add three “Missing Pages”—visually subdued essays (at least in comparison to the rest of the zine) that detail their struggles with sexual assault, harassment, and depression. In one, they recount their own experience of assault and subsequent shunning by their community and friends after disclosing what happened. These essays bring Lawhead’s personal narrative into sharper focus, bridging the gap between the cartoonish aesthetic and Lawhead’s underlying reality of each page.

Every aspect of the zine, from the juxtaposition of playfulness and violence to its mimicry of a computer interface, is intentionally crafted to enhance its emotional impact. Lawhead’s choice to have the narrative communicated through various pop-up computer windows draws on hypermediacy, a term coined by media theorists Jay Bolter and Richard Grusin in their 1996 article “Remediation.” Bolter and Grusin write that “in the logic of hypermediacy the artist...strives to make the viewer acknowledge the medium as a medium and indeed delight in that acknowledgement. They do so by multiplying spaces and media and by repeatedly redefining the visual and conceptual relationships among mediated spaces--relationships that may range from simple juxtaposition to complete absorption.”

By communicating its narrative in digital fragments, the zine intensifies its message—that trauma defies tidy narratives and resists easy consumptions. Lawhead’s refusal to package their narrative into a neatly consumable format forces readers to engage with pain on its own terms. The zine’s fragmented, chaotic structure mirrors a survivor’s perspective, offering a counter-narrative to linear stories of recovery. The structure stands as a personal archive of survival and testament to persistence, all taking place within a desktop interface.

The final page, Missing Page 31, reveals Lawhead’s family history as refugees from a war-torn country. Facing genocide, Lawhead and their surviving family fled to the US, where Lawhead grew up with internalized stories of fear. However, it is precisely this threat of being voiceless that Lawhead draws on for their affirmation: “My family history is that of somehow surviving, somehow prevailing for the basic right to exist.” They draw on the desire for their family to live through them as a reason to keep on going. By the zine’s conclusion, Lawhead ushers the reader to witness the bare truth of any story of survival: “We are human too. We existed too.”

Post a comment